Export shipments of indian soya bean bean

Due to some sizeable claims involving shipments of soya bean meal from India, the West of England has investigated the cause of self-heating in transit of such cargoes. This can lead to varying degrees of discolouration and/or deterioration of the product on out-turn.

The majority of meal in question has been loaded at ports in the North West state of Gujarat, principally Bedi Bunder, Mundra, Bhavnagar and Kandla but with some tonnage being taken at Mumbai and at the East coast ports of Kakinada and Vishakhapatnam. The majority of export is to South East Asia, and the particular claims investigated were related to cargoes delivered to Shekou, Lianyungang, Zanjiang and Nantong in China, Inchon and Kunsan in South Korea and Kashima, Kagoshima, Shibushi and Hachinohe in Japan.

The method of shipment of the cargo can vary. Normally, the meal is bagged in jute sacks at inland producing mills which are then taken to the vessel and emptied into the holds. However, the meal may also be retained in bagged form for ocean carriage. In addition, it has been known for shipments to arrive from the mills by lorry in bulk and be transferred direct into ships' holds by means of canvas slings.

Although there are both yellow and black varieties of soya bean, cultivation in India now mainly concentrates on the yellow variety. The soya bean itself is normally processed at source, using a solvent extraction method to produce the oil which is retained exclusively for domestic consumption. The remaining "meal" is then toasted under what should be carefully controlled conditions of temperature and time. It is then used for blending with other ingredients to produce compound feed for animals, especially poultry.

The normal colour of the meal after toasting ranges from a bright yellow to a dull buff yellow, but if over-toasted, the meal can be a distinctive brick red or brown colour. Besides over-toasting, the major source of discolouration is intrinsic heating associated with excessive moisture content. The critical moisture content of meal for satisfactory medium to long term storage is about14%. However, in practical terms a figure of 12% is deemed to be prudent for safe carriage aboard ship.

Above this level, increasing rates of microbiological heat generation may occur. Depending upon the degree of moistness, attained temperatures can be in the range of 45°C to 70°C. Furthermore, once the temperature of the meal has risen above a certain level, a secondary chemical heat generating mechanism can be triggered with temperatures reaching in excess of 100°C, which in turn may lead to dark brown or black discoloration.

When substantial heat-discoloration occurs in soya bean meal to the extent of it becoming black, the quality of the protein may suffer appreciably, especially in respect of its nutritional value.

In the particular cases investigated, the cause of the excessive moisture has been attributed to the unseasonally heavy rain during 1997 in the main producing areas around Madhya Pradesh. At the subsequent harvest in October/November of that year, substantial quantities of the beans were considerably higher in moisture content than usual. This was compounded in some instances by inadequate rainproof storage for the harvested beans and insufficient bean drying capacity in the processing plants. Unsatisfactory drying appears to have precipitated many of the subsequent claims.

It is widely accepted amongst technical experts that when soya bean meal with an excessively high moisture content is loaded aboard ship, there are few practicable means open to the master with regard to either ventilation or other measures to exercise any significant control over the degree of self-heating in transit. Therefore it is essential to prevent meal being shipped that may suffer from self-heating through it being over-moist.

Although contracts for soya bean meal exports in India normally call for joint sampling and inspection by buyers' and sellers' surveyors, this is rarely implemented with the result that one survey company often acts for both. This arrangement is clearly unsatisfactory, and we recommend that an independent surveyor is engaged to safeguard the interests of the ship.

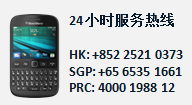

Accordingly, in an effort to minimise the possibility of large claims, the Club will bear 50% of the costs of a pre-loading survey in Indian ports where soya bean meal cargoes are to be loaded, until further notice.

The independent surveyor should be instructed to take note of the following:

- If not already provided, a written specification of the soya bean meal should be obtained before loading. A copy should be retained on board.

- As far as possible, the inspection and testing process should be started prior to the commencement of cargo operations.

- Although it is clearly impossible to sample and inspect more than just a small proportion of the bags in any one shipment, diligent sampling must be carried out as far as is reasonably practicable. The normal procedure is to draw composite samples from between 3% to 5% of the total bags, ensuring that samples are not taken only from peripheral bags in the stacks (which may be drier as a result of their position).

- The representative samples must be sent for laboratory analysis to determine moisture content, taking the criterion of acceptance as being a maximum of 12%.

If any parcel is found to have an excessively high moisture content or if the colour differs from that specified, it should be rejected and the local Club Correspondent notified.

In addition, the Club's Loss Prevention department may be contacted for advice if required.